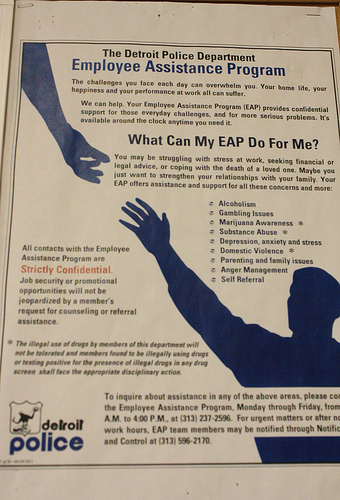

A flyer hangs in police headquarters advertising the Employee Assistance Program that serves Detroit police officers in need. Photo by Emily Canal

Airforce veteran Erik Cox was in his early 20s and new to the Detroit Police Department when he began to feel troubled. He was baffled by his depression since he had a job in his hometown and was no longer serving in the Persian Gulf. But images from work triggered nightmares, and talking to his friends didn’t help. He couldn’t get over what people were capable of doing to each other. One afternoon he took his service weapon to a vacant lot and planned to shoot himself. He wanted to be sure his death was definite, and wasn’t going to risk a suicide attempt where he could be revived.

“I wasn’t popping pills, I wasn’t going to do nothing like that,” said Cox, 44, now a sergeant with the Detroit police. “Nothing that I could possibly be saved from. It had to be a sure fire way.”

It was then Cox thought about his mother and four sisters, and what they would think if he committed suicide. Cox put the gun down, went home and got help.

But far too many officers do not follow in Cox’s footsteps, and according to a recent study, Detroit has the highest rate of suicide among police officers than any other city in America. Dr. Bengt Arnetz, the director of the Division of Occupational and Environmental Health at Wayne Sate University School of Medicine, said he found 28 per 100,000 officers kill themselves a year. The rate in New York City is 15 per 100,000, 18 in Chicago, and 20 in Los Angeles. Commander of Internal Controls Brian Stair, 43, said more uniformed police officers kill themselves than those who die in the line of duty.

Although Detroit Police Department dispute the statics- placing the figure at nine suicides in the last 10 years – what’s evident is that suicide is a threat to the city’s police force.

Officers said what makes the issue so specific to Detroit is the combination of high crime rates, personal issues and the constant availability of weapons. Homicide has increased by 20 percent this year, according to the Detroit Police Department.

“When they commit suicide they choose to do that, it’s a selfish act on their part,” said Stair, who cited relationship issues as the main reason behind the self-inflicted violence. “Its not a bad guy taking someone’s daddy or mommy away.”

Lt. William Petersen of the Detroit Police Department said disturbing images and pressure, could turn into stresses for officers. He said this leads to bigger problems, like depression and suicide, and readily available guns only adds to the problem.

Lt. William Petersen of the Detroit Police Department admires photos of his family and said her personal life helps keep him calm after a stressful day at work. Photo by Emily Canal

He said most officers shoot themselves in the head or mouth.

“When things reach that point and if the gun wasn’t part of your body or an extension of it, maybe it wouldn’t happen,” Peterson said.

And many officers, like Cox, do not capitalize on the confidential treatment options available.

Before Cox contemplated ending his life, he confided in fellow officers that he was depressed. But Cox said talking to other cops is not beneficial and usually turns into a contest of who has seen worse.

“I learned over time that cops aren’t the best, you should really get professional help,” Cox said. “One of the things we always do is try to outdo each other and talk about the most graphic scenes.”

Sgt. Carrie Schulz, 34, said most officers see the gruesome aspects of the job as a stamp of approval and worry that by voicing their depression they will lose their creditability.

“They are worried about undoing that approval and might not talk about it,” Schulz said. “They don’t want people to think they are chicken, they think it can be career suicide.”

While officers are aware that confiding in partners is not the best method, they still do not seek the help of professionals. Posters advertising the aid of the Employee Assistance Program hang around the various Detroit precincts, but very few call the confidential outlet.

The service offers recommendations and treatments for alcohol and drug abuse, couples counseling, depression or PTSD. But officers must initiate the call and cannot be mandated unless they are asked to attend for anger management or alcohol counseling.

The Detroit Police Department also has a Chaplin Corps, a group that will sit down with officers and discuss any issue. Officer Dwayne Deck is the liaison between police officers and the Chaplin Corps.

“Its good to have them get it off their chest, when you go home, your family doesn’t understand exactly what you’re saying and can’t sympathize with you,” Deck said. “Nine out of 10 times, their spouse isn’t going to understand, but Chaplains do ride-alongs and understand a little bit better than spouses.”

Deck said there are 45 chaplains on staff, but the corps faces the same problem as the Employee Assistance Program, very few utilize the service.

“It kind of bothers me sometimes that I can’t help them,” Deck said. “They don’t take advantage of what we have and some don’t want the Chaplains around.”

Cox said most officers refuse help because they don’t want to look weak and try to uphold the “tough image” that comes with the job.

“There is a perception that we are tough guys and don’t need that type of thing,” Cox said. “That’s why a lot of people don’t ask for that type of assistance.

But Cox eventually did.

“For a year and half I sat on the couch and it helped me to deal with a lot of stuff a lot better,” said Cox, who sought private therapy. “Some of that is hard to forget and when you close your eyes at night and drift off into slumber it has a way of creeping back in.”

Because most officers do not seek professional help, Petersen believes a preventative measure is needed to combat the “macho” outlook many cops uphold. He said by telling students in the police academy what they will see and breaking down the tough ideals, officers could lead healthier personal lives and subsequently lower the rate of suicide.

“Young officers need to be taught that they will encounter those things, not that they probably will, not that they might, but that they will,” Petersen said. “Consequently, they have to be taught how to handle them and should be taught those things right from the beginning.”

Arnetz, who studied police suicides in Sweden, is crafting a study in Detroit that hopes to decrease the suicide rate through preventative mental training. Arnetz hopes to demonstrate that by teaching stress management and emotional regulation during initial training, officers will think clearly and recover quickly from trauma.

“We know they are going to be exposed to trauma and they are prepared tactically,” Dr. Arnetz said. “They are never mentally prepared even though we know they are going to be exposed to violence.”

He surveyed local officers and found the 10 most stressful scenarios they could face on the job. Car chases, bank robberies, dead children and domestic violence ranked the highest. He takes officers through the protocol they are taught, trains them to focus on the task at hand and how to cope with disturbing images.

“Together with police skills we teach the officers to relax and once you mentally relax you can create the scenario in your head,” Arnetz said. “We tell them how to deal emotionally and not get overstressed.”

Cox believes the macho attitude is one of the main factors behind officers refusing to get help. And while he hopes that it can be resolved, he is skeptical that the mentality will dissipate.

“Six friends of mine have committed suicide,” Cox said. “I am tired of counting now.”

Comments

Great job Emily! Congratulations!

Great article! You tackled a tough issue, and really brought the issue to light through the personal story Cox shared with you. Your lead really reeled me in. And then you just really hit it with your nut graph. Awesome job…