A Franklin Delano High School’s students drawing of the 9/11 attacks hangs in a social studies classroom. The Bensonhurst high school teaches 9/11 every year. Photo by Julie Liao.

It’s just after noon on Friday at Franklin Delano Roosevelt High School, in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. Twenty seven students swarmed into their stuffy, 11th grade social studies class.

This was their last social studies class before the 15th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks that changed their city and their world. Michael Scherer, 38, their teacher, planned to teach his annual 9/11 class as he had been doing for the past five years.

“Raise your hand if you heard the word virtue before? What does it mean?” he asked the class.

He defined virtue as “doing what is right for the common good and expecting nothing in return.”

Scherer started a discussion about whether people do good deeds out of their natural kindness or for payback. He asked the students for their thoughts and the response was spilt down the middle.

“The point of today’s lesson is to kind of prove that wrong,” he said of those who believed payback was a reason to do good. Scherer had a very personal story to share about virtue and doing good for nothing in return.

Scherer’s father-in-law, Vincent J. Albanese, a veteran firefighter, was among thousands of heroic first responders, who rushed to the World Trade Center and helped to rescue trapped workers after the two planes crashed into the towers. For several months after the attack, he supported clean up efforts at ground zero.

But the toxic dust made Albanese sick, Scherer said. In 2010, he died of bladder cancer. He was 63.

“I watched him pretty much die,” he said.

Scherer isn’t the only teacher who emphasizes 9/11 education at the school. All the social studies teachers at FDR high school are required to teach 9/11 in their curriculum.

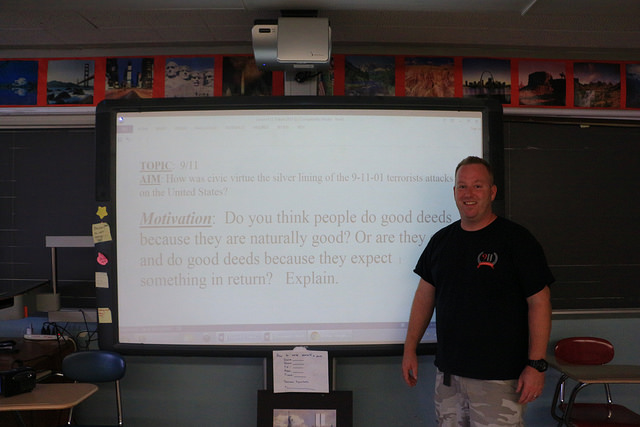

Michael Scherer, 38, social studies teacher of Franklin Delano Roosevelt High School. He has been teaching 9/11 to high school students for five years. Photo by Julie Liao.

In fact, the first comprehensive 9/11 education plan for teenagers in New York City was released by a nonprofit group in 2009. Two years later, cooperating with the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, the Department of Education of NYC provided online teaching materials for students from kindergarten to high school. Through stories, videos and interactive activities, the students would learn about the attacks in four parts, “community and conflicts”, “historical impact”, “heroes and services” and “memory and memorialization”.

But since it is not mandatory, not all schools teach it.

FDR high school administrators believe it is an important part of history and should not be ignored.

“We teach them those events and also some of the historical context in which they occurred to raise awareness about not only global terrorism,but about the resiliency of the American people after those events occurred,” said Christine Imbemba, the assistant principal of this school as well as a social studies teacher.

But 45 minutes is not enough to study 9/11. Although both Imbemba and Scherer said they are more than willing to spend the whole school day teaching 9/11, they have to comply with the school’s curriculum schedule.

After the discussion, Scherer had his students watch the documentary, “The Man in the Red Bandanna.” It is the story of Welles Crowther, 24-year-old equities trader working on the 104th floor of the World Trade Center during the attack. Somehow he found an escape route and led three trips up and down the stairs, even carrying survivors. His body was found in the rubble six moths later.

“… like what if that was me, what if that was my son, what if that was my brother,” said David Ismailati, 16, a student about the documentary. The teen believes terrorism is still a big threat.

Ismailati said he may do an oral history as his 9/11 homework assignment. His father was working about ten blocks away during the attack.

“He had to walk all the way from around the World Trade Center back to Brooklyn because there was no subway,’’ he said. “He came back covered in debris completely.”

Despite the limited time and resources, Scherer said he believes his students will understand his theme of selfless virtue and 9/11.

“I know it was just like a small message, but I think it might resonate,” he said.