The post Opioid Usage in Philadelphia Leads to Increase in HIV Diagnoses appeared first on Pavement Pieces.

]]>Anyone familiar with Philadelphia knows Kensington Avenue as an open-air drug market. Tucked under the elevated train tracks in North Philadelphia, business is open, even in the pouring rain on a recent Sunday afternoon. Nearly every drug, including heroin, fentanyl, marijuana, K2, and benzos, can be bought under the dingy underpass, in front of rundown stores and corners piled high with garbage.

Despite the occasional presence of a police car, dealers sold openly, ducking under awnings and in doorways — avoiding the rain, not law enforcement. Users didn’t even bother to go behind closed doors before cooking and injecting their drugs, completely unconcerned with anyone who might be watching.

While the opioid crisis in Philadelphia has been a status quo for years, this endless drug use is causing a new problem: an increase in HIV rates for the first time since the mid-2000s.

“We don’t need another health epidemic. We have enough with addiction,” said Carol Rochuster, founder of Angels in Motion, an advocacy organization that does outreach and policy work for those who use drugs. Seven years ago, her own son was living on Kensington Avenue, trapped in his own addiction. He’s currently in recovery, but the isolation and conditions on Kensington Avenue inspired her to start talking to those on the streets and try to help. Since then, she’s spent almost every day since then working with opioid users, offering counsel and conversation, helping them find spots in treatment centers, and generally doing everything she can to help put a dent in Philadelphia’s opioid epidemic.

A woman with track marks on her legs runs past another man on Kensington Avenue, Philadelphia. Photo by Kerry Breen.

“Just last week, one of my people said to me ‘I just [tested] positive for HIV.’ It is increasing. It’s just a small percentage, but it is still an increase – it hasn’t increased in years, and now all of a sudden it’s increasing. That could spiral out of control.”

The increases have been small so far, according to James Garrow, Director of Communications at Philadelphia’s Department of Public Health. Diagnoses in the city were decreasing until 2016, when there were 27 diagnoses of HIV among those who use drugs. From 2016 to 2018, the number more than doubled, with 59 new diagnoses among people who inject drugs. The amount may be small, but Garrow describes it as an “outbreak.”

The Trump administration has announced a plan to combat HIV, with the goal of almost completely eliminating the illness by 2030. The plan would target 48 counties where HIV is spread at the highest rate, including Philadelphia, as well as focusing on seven states that have high rates of HIV in rural areas. The plan will have almost 300 million in funding, which is one of the largest increases in HIV funding. However, advocates and experts worry that the plan falls short, and will not reach the people who need it most, including those in Kensington.

“There needs to be a lot more consideration of ‘How do we reach to that set of people that isn’t just able to engage in the healthcare system as easily?’,” said William McColl, the Vice President for

Policy and Advocacy at AIDS United, an organization that works to end AIDS in the United States. “Homelessness is a primary example, but also people who are involved with drug use, that aren’t necessarily seeing [doctors]. I do think they’re going to have their work cut out for them in reaching all of the people that truly need to be reached.”

Garrow is also concerned that President Trump’s other healthcare policies might affect the access that would be necessary for this plan.

“What’s been proposed isn’t really new, and the administration’s assault on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would probably undercut any gains,” he said. “Health insurance is necessary for many people to get the care that they need to treat HIV infection and prevent the infection from spreading to others.”

Other proposed plans have included safe injection sites and needle exchange programs, but these plans have received significant amounts of backlash. Safehouse, a safe injection site that would operate in Kensington, has been tied up in legal battles with the federal government, and needle exchange programs are not the most popular solutions.

Carol Rochuster, founder of Angels in Motion, an advocacy organization that does outreach and policy work for those who use drugs, sits in the Fishtown Diner. Photo by Kerry Breen.

There’s also a focus on clean equipment, even among the trash-ridden streets of Kensington. Groups like Rochuster’s Angels in Motion do their best to provide not just clean needles and cookers, but also information on why using it is important.

“If you don’t keep people alive, they can’t make it to recovery,” said Rochuster, whose organization has begun doing mobile needle exchanges to reach as much of the city as possible. “HIV has increased in the city, and the access to needles hasn’t. They’re still in one location, but South Philly needs it, Northeast Philly needs it, Southwest — they all need access to free needles. You need clean needles. And not just needles – supplies, cookers, you need everything.”

Beyond these efforts, Philadelphia is already doing many of the things the administration’s plan outlines, including funding programs and outreach efforts.

“We are expanding syringe exchanges, working to increase access to PrEP, and working to link people who inject drugs to medical car to ensure viral suppression,” said Garrow. Rochuster says that in her own advocacy, she focuses on making sure that the people she talks to know how important HIV medications can be.

Even with the efforts of health departments and harm reductionists, Kensington seems as stricken as ever. Dealers huddle under the awnings of drug stores and takeout Chinese restaurants; an encampment filled with users sits directly across from a mobile unit run by Prevention Point, another organization that does outreach with opioid users. A police car with its sirens off drives across the intersection, not even acknowledging the open sale and use of drugs.

Despite the police presence, crime rates in Kensington are high, and drug sales and use continue with little enforcement. Photo by Kerry Breen.

However, to Rostucher, the solution is not to abandon areas that seem hopeless, but to keep trying, to break through the barriers of stigma and isolation that surround such neighborhoods.

“I started this because of my son. I would go down to find him. I just wanted him to know I loved him. While going down and looking for him, I saw so many lost individuals, so many lost souls,” she said. “And then I realized that the isolation is just feeding this disease. The more I went down, the more I could see — the isolation just took people down deeper into their addiction, and they were so alone, and they just keep going deeper.”

The post Opioid Usage in Philadelphia Leads to Increase in HIV Diagnoses appeared first on Pavement Pieces.

]]>The post Aging with HIV appeared first on Pavement Pieces.

]]>by Megan Jamerson

Frequently the problems of middle age are something young people dread. For one group of men, getting to discuss those issues is a remarkable gift.

“I thought I wouldn’t see 25, but I’m going to be 48 in two weeks,” said Kevin Oree of Kips Bay in Manhattan.

Oree is HIV positive. He along with two other AIDS survivors, Perry Halkitis and Jim Albaugh spoke in a forum cleverly named “We Aren’t Dead Yet! What Do We Do Now?”. The forum held by the Gay Men’s Health Crisis(GMHC) in their Chelsea office yesterday evening, sought to sort out the problems middle age men with HIV face.

The topic attracted a jovial crowd of mostly men, but when it came time for the veterans of the disease to tell their story a hushed reverence fell over the crowd.

Oree was 19 when he contracted HIV, Halkitis 25 and Albaugh 26. It was at the height of the AIDS crisis in the late 1980s and before the advent of HIV medication. They had little hope for anything more than a grim future with that diagnosis.

“If I’m HIV positive, I’m dead in two years,” recalled Oree.

Two years to live was the typical prognosis. Then in the mid 1990s, an anti-viral medication became available making HIV a manageable disease patients could live with for many years. Now nearly 30 years later, survivors face middle age knowing very little about what to expect.

Perry Halkitis moderates the Gay Men’s Health Crisis forum on aging with HIV

Photo Credit: Megan Jamerson

“We are unfortunately the first of many generations to age with this disease” said Halkitis.

Halkitis, the GMHC forum moderator, is an NYU professor, author of “The Aids Generation: Stories of Survival and Resilience”. Halkitis, 51, like Oree and Albaugh, lived an adult life defined by the disease.

“Almost every generation faces a crisis. The ones that preceded us faced Vietnam and World War II. This was our crisis, very much a war against a silent and deadly enemy,” said Halkitis.

Which is why he believes this forum is of such high importance. He hopes the community of survivors, especially from the AIDS crisis generation, can come together and create a model for the next generation to deal with aging more successfully.

The issues raised during the discussion were varied. They spoke of the positive and negative health benefits in the changing medical landscape since the Affordable Health Care Act; learning to deal with social stigma; and the troubles of holding a steady job while battling illness.

The most frequently raised issues were of depression, isolation, and the frustrations that come with the disease.

“Sometimes it’s just easier to stay in your apartment away from people and not deal with things. It’s a struggle to get out every day,” said Albaugh. The crowd murmured in agreement.

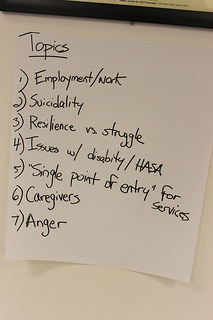

Topic points discussed during the Gay Men’s Health Clinic forum on aging with HIV

Photo Credit: Megan Jamerson

Albaugh, 53, had his HIV progress to AIDS in 1990 and experienced a long and difficult struggle with depression ever since. Today he is in much better health, but always mindful of the challenge of survival.

Because HIV does not have a cure these men have learned to come to terms with its never ending presence. Over time they became resilient to its permanence.

“I call it my guest that occupies a lot of space but pays no rent,” said Oree with a smile.

The forum ended with a long list of ideas GMHC plans to take into brainstorming sessions to create new programming to meet the needs of the aging community. They hope the model they create is something worthy of being used nationally.

“We can come forward as proud models and bridge the gap to the next generation as they fight this disease,” said Halkitis.

The post Aging with HIV appeared first on Pavement Pieces.

]]>The post Aging with HIV appeared first on Pavement Pieces.

]]>When Richard Kelso was diagnosed with HIV in 1987, he was devastated. In the late 1980s, scientists and physicians were still trying to understand the virus. The available medications they used to treat HIV were often toxic and untested.

But Kelso’s devastation quickly gave way to hope that he could live with this illness. The clinician at the Chelsea Health Clinic in New York, where he was diagnosed, gave him a stack of pamphlets about HIV as well as support groups he could attend.

“Even though I was frightened of the prospects, she made it seem like there was a possibility that it was not a death sentence,” said Kelso, 71, sitting on a piano bench in his Chelsea apartment. “There was something I could do that could be helpful and I didn’t have to just go home and wait to die.”

For the first five years after he was diagnosed, Kelso treated himself with a regiment of Chinese medicines and herbs to boost his immune system. It was the beginning of a series of experiments in staving off the virus. Eventually he began taking pharmaceutical drugs to manage his illness. He says he has never been hospitalized because of HIV.

“The medications have been miraculous,” said Kelso. “As somebody who is aging with HIV, the biggest hurdle is to just deal with the apprehension about death and my health from day to day.

Richard Kelso,71, has lived with HIV for 30 years. He says becoming an expert on your own health is a survival strategy. Photo credit: Leticia Miranda

By the mid-1990s, treatment for HIV drastically improved which meant that people like Kelso had the chance to live a longer life. Now he is one of a growing number of people who are living longer with HIV as treatments have become more effective. But even with these advances, patients with HIV and their physicians have a more complex challenge ahead of them as they try to treat HIV along with the typical illnesses that come with aging.

Many people aging with HIV face what clinicians call “multi-morbidity,” which means the patient has multiple incurable health issues that are treatable. In Kelso’s case he has to be treated for HIV as well as cholesterol, which is a result of aging not the virus or medication. Traditionally, doctors are trained to treat HIV apart from other health conditions. In geriatric medicine, doctors are trained to work with patients older than 65 with multiple health issues but may not know how to treat HIV along with those other illnesses.

This kind of treatment is essential to people aging with HIV. They are at a higher risk for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, early frailty and kidney failure. The medicine to treat these could aggravate the HIV and the HIV treatment could have a damaging affect on their other health conditions.

“We call it going from the silo of treating HIV and now going to treating the whole person at once,” said Steve Karpiak, senior director for research and evaluation with ACRIA, an HIV research organization. “The question is what is the primary disease that has to be managed? The reality is they all have to be. It’s a balancing act and it’s best done through a team approach with the patient.”

But health care is not the only issue confronting some people aging with HIV. They are often more likely to have weaker social networks than people who are not infected with HIV. Many of them are isolated from their families because of their illness or sexuality. The networks they do have are mostly other HIV-infected people who may not be able to provide the kind of long-term care they will need.

“Some live alone and don’t have a partner,” said Bill Mendez, a case manager at Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders, who runs a support group for people aging with HIV. “There’s a lot of anger and a lot of resentment towards their family or siblings. They don’t hear from them. They don’t speak to them. They come here for support.”

Kelso has over 30 years of being his own advocate and has created a healthy and full life for himself. Over the years he has had to become an expert on his own illness.

“We treat our doctors as consultants not as a god who dispenses medicine,” said Kelso about the SAGE support group. “You have to take control and be your own best advisor. Don’t take what the doctor says as a mandate that you have to adhere to because sometimes they don’t know. As new medications come along they dispense them but they don’t know what the long-term effects are. It’s up to you to sort of keep on top of that.”

The post Aging with HIV appeared first on Pavement Pieces.

]]>The post Hip-hop artists raise HIV/AIDS awareness within African-American community appeared first on Pavement Pieces.

]]>

Maria Davis hosts M.A.D. Wednesday's, an event held on the second Wednesday of every month to feature new artists and raise awareness about HIV/AIDS in the African-American community. Photo by Jasmine Brown.

Beau Bostic stepped onto the stage of a Harlem nightclub with the swag of a hip-hop artist. In a spotless oversized white T-shirt and baseball cap, Bostic grasped the microphone and began to spit out lyrics about the trials of street life. At the front door, patrons paid a $10 cover charge and picked up free condoms.

Bostic is just one of the half-dozen artists featured recently as part of “M.A.D. Wednesday’s,” a show held on the second Wednesday of every month at the Shrine World Music Venue at 2271 Adam Clayton Powell Jr Blvd. in Harlem to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS in the African-American community.

Maria Davis, 51, an AIDS/HIV activist who hosts the monthly event, started M.A.D. Wednesday’s in the 1990s to provide a space where young R&B and hip-hop singers and comedians could hone their skills. It has showcased artists such as Brandy, Monica, Jay-Z, and the late Bernie Mac.

Davis still holds the event to promote new talent, but after being diagnosed with AIDS in 1998, she incorporated HIV/AIDS awareness into the show. She now hands out condoms and raises funds for the AIDS Walk in addition to letting patrons have a sneak peak at the newest up-and-coming artists.

“Young people are so heavily informed by the hip-hop community,” Davis said. “I think that it would be a great thing for them to not only give the message of safe sex, but to give hope to the hopeless.”

Bostic, 30, of Red Hook, Brooklyn, is a hip-hop artist who heard about the event through Facebook.

He said he’s grateful to people like Davis who teach him about the risks of having unprotected sex.

“Sometimes you get into situations where you may be on the way to being intimate with a female and without a condom,” Bostic said. “It’s only through these outlets, news papers, radio, magazine, TV, it is only through these outlets that those thoughts start to rush into your head and you are like, ‘You know, let’s just wait. Let’s just do the right thing.’”

Davis was a successful hip-hop promoter, soon to be featured on the debut album of rapper Jay-Z when she received a letter that changed her life. She had taken an HIV test as part of an application for a life insurance policy and the results came back positive.

“I thought that my life was over because at the time when I found out I was HIV positive in 1995, medications weren’t even out yet, they were just starting to get a handle on the disease,” Davis said. “At that time we thought that HIV was a gay white man’s disease.”

Davis contracted HIV unknowingly from her boyfriend, a man she thought she was going to marry. Three years later, she was diagnosed with AIDS.

“I was scared and afraid and thinking about death,” she said.

Her health took a turn for the worst. The disease was eating away at her body and she was rapidly losing weight. Davis said she was on the verge of death when she turned to the Bible for help.

She became an AIDS activist soon after and has since dedicated her life to teaching African-Americans about the disease.

HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects African-Americans. According to the U.S. Office of Minority Health, under the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, African-Americans were nine times more likely than whites to be diagnosed with HIV in 2008. And while African-Americans represent just 12 percent of the U.S. population, they accounted for 48 percent of all new HIV infections in 2009, according to the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Davis said she still encounters many myths about HIV/AIDS.

“There are still people that think that AIDS is a curse, that people that get AIDS deserve to get AIDS, that their behavior should have been different, that they are promiscuous,” Davis said.

The Centers for Disease Control attributes the high rate of HIV to lack of awareness, limited access to healthcare and HIV prevention education. The CDC also calls attention to the stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS in the African-American community, which prevents many at risk individuals from seeking testing and counseling due to a fear of being shamed.

Deborah Levine, Vice President of Community Development for the National Black Leadership Coalition on AIDS based in New York City, called the numbers “staggering.”

Levine said it is important to talk outside the box about sex and sexuality, and to take the message from inside the doctor’s office to more unconventional venues.

“It starts with prevention, it starts with telling people about what the epidemic is, how they can not be come infected, where they can get tested and if positive where they can get treatment,” she said.

The post Hip-hop artists raise HIV/AIDS awareness within African-American community appeared first on Pavement Pieces.

]]>The post Living with HIV/AIDS: AIDS Researchers Say Work is Personal appeared first on Pavement Pieces.

]]>

Michael Chung, an acting instructor in the Department of Allergy & Infectious Diseases at University of Washington, has lived in Kenya for the last six years doing work through the Center for AIDS Research.

Dr. Stephen Brown was living in Philadelphia when his friends began to die.

Brown, the director of clinical research at the AIDS Research Alliance (ARA) in California, knew then that he wanted to join the fight.

“I ended up taking a research fellowship at the University of California in San Diego, in the HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center,” he said. “I basically lost almost all of my cohorts and I decided I wanted to do what I could to start attacking this disease.”

Brown is one of hundreds of researchers studying AIDS in the United States. And for many of these scientists, doctors and lab technicians, the work is personal.

AIDS is a medical condition resulting from the progression of HIV. Simply put, it knocks out the body’s immune system, leaving it vulnerable to a variety of infections. Once-exotic diseases or otherwise harmless bacteria became life threatening. Death used to be assumed. But the rules have changed, thanks in large part to antiretroviral drug therapies. These drugs — often taken in “cocktails” of three or more medications (known as HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy), significantly reduce the amount of HIV cells in the body.

As the course of the disease has changed, so has the research. Brown used to conduct clinical trials involving dementia, which was a big issue for people with HIV/AIDS prior to antiretroviral therapy. He now studies medical interventions to treat, prevent and eventually cure AIDS. Founded in 1989 by a group of physicians in Los Angeles, ARA is about sharing efforts and information for a more efficient process. In the beginning, Brown recalled, they considered everything from shark cartilage to garlic extracts.

“People were really, really desperate,” he said.

The group is now working on a drug called prostratin, used in traditional Samoan herbal medicine for the treatment of yellow fever. This plant extract may help attack “viral reservoirs” in HIV-positive patients who are being treated with antiretroviral drugs.

“There’s a pool of cells that remain infected,” Brown said. “So the idea is how do you try to get at these infected cells, this reservoir.”

Though the medical research is exciting, what really makes a difference for Brown is putting his research into practice. He once treated a patient with neuropathy, a painful condition affecting some HIV-positive patients that causes a burning sensation in the hands and feet. The man had to wear flip-flops because he was in so much pain. But after treatment, he returned to the doctors wearing his cowboy boots, which he hadn’t been able to do for years. For others, treatment has literally pulled them from the brink of death.

“We had a patient who’d been on his deathbed for a really, really long time,” Brown said. “We were doing a study for Merck of an integrase inhibitor, which is a new kind of antiretroviral. For the first time in 10 years, this person went undetectable. He was able to work out again, his energy level came up.”

But for every success story, there are frustrating losses.

“There’s people who just missed it by a year or two,” Brown said. “One of my best friends ended up dying in 2002. He needed the next set of new medications and he just didn’t live long enough to see this new round of medications come out.”

Though the vaccine study that ARA conducted nearly two years was unsuccessful, a vaccine isn’t out of the question. And like the vaccine for cervical cancer, it may be administered as a matter of course.

“I anticipate it would be the kind of thing you would give adolescents before they become sexually active,” Brown said. “There’s some people that feel you’re sending the wrong message to children, but I think should a vaccine like this come out and it worked effectively, most physicians or researchers would make sure their kids got it.”

But the benefit of such advances comes to developed countries first. Dr. Titilayo Abiona, director of research at the HIV/AIDS Research and Policy Institute at Chicago State University, has seen the disease in the U.S. and Nigeria. She knows firsthand how profoundly HIV-positive patients are affected by treatment and testing.

“Here in the U.S., treatment is available to anybody,” she said. “If you test positive, you can access treatment. In Nigeria, it wasn’t like that. When I left in 2006, there were a lot of people who knew their status who couldn’t get care.”

Abiona said many people can barely afford the necessities of life, much less medications. She once raised money so a patient could receive HIV treatment, but the woman spent the money on food and other basics instead.

Abiona said that free HIV testing in the U.S. also encourages more people to learn their status. When she was in Nigeria, testing was limited and it cost the patient money. Many people figured that if they had to pay for a test, and then discover they had a disease they couldn’t get treatment for, then why bother knowing?

“There’s a lot of denial about HIV and, of course, the stigma is rife,” she said. “And there’s stigma here too.”

She also said there may be a connection between HIV infection rates and religion in the Nigerian population — a phenomenon that requires further exploration.

“When I was doing HIV testing for pregnant women in two communities in Nigeria, one was a predominantly Muslim community, and I didn’t get one single case of HIV there,” she said. “In the other area, where they are more Christian and more liberal — yes, there were cases there.”

U.S. research organizations are sharing information here and abroad in a way that was sorely lacking when the disease first emerged. Michael Chung, an acting instructor in the Department of Allergy & Infectious Diseases at University of Washington, has lived in Kenya for the last six years doing work through the Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), which partners with the university. For the doctor, this is an ideal situation.

“The large majority of people who are affected are in poorer countries,” he said, “I wanted to do research that would have an impact on people in these countries and would allow me to practice medicine as well as do research.”

After practicing medicine in refugee camps, Chung knew he wanted to help people in resource-limited settings. His work in Kenya, so desperately needed, also answers important questions about treatment for patients in the United States.

“For example, starting out doing programmatic work in terms of setting up an HIV clinic in Kenya answered questions like: How do we keep people on medications for a long period of time,” he said. “I was able to ask better questions or more relevant questions, rather than ivory tower questions that were academically interesting but wouldn’t have any impact on the ground.”

As more people survive with HIV, a new cluster of symptoms and complications arise. Chung has studied behavioral interventions to enhance medications, in addition to implementing cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women. Because many people no longer die of AIDS, Chung said the next big killer among women infected with HIV could be cervical cancer.

The clinic Chung helped establish in Kenya began with one woman, Grace, an HIV-infected woman who worked with Chung when he first arrived in 2002. It was obvious that she was dying of AIDS. She had skin cancer, fevers and other complications that kept her from work. Chung got $1,000 — enough money to treat her for a year. Grace’s 9-year-old daughter was also infected, and she wanted the treatment for her. With the help of additional funding, both mother and child are healthy and continuing their lives. Chung said this is a common problem for cash-strapped Kenyans who are dealing with multiple infected family members.

Based on this success, Chung received more funding and eventually set up the Coptic Hope Center for Infectious Diseases in collaboration with the Coptic Hospital. The clinic has seen over 8,000 patients and placed more than 4,000 people on antiretroviral medication.

“Just from treating Grace, this has turned into this huge treatment center that is really helping thousands of people,” Chung said.

But with so many patients, people sometimes disappear and are never heard from again. That’s what happened to Rosabella, a patient whose children both died of AIDS. She eventually stopped coming to the clinic, and Chung thinks she is probably dead, as well.

The idea that a person infected with HIV can now live a long and relatively normal life is inconceivable to people both in the U.S. and overseas. Chung said it’s one of the biggest misconceptions he has encountered. When a patient who had lived on antiretroviral medication for over a decade spoke to a group of Kenyans, Chung recalled that it sent a shock through the crowd. After so much death, they were amazed that HIV/AIDS could be treatable.

“There’s a lot of people who feel that HIV is a death sentence,” he said. “But the reality is that so many people have survived for so long on antiretroviral therapy that we can treat it as a chronic disease now, like diabetes or hypertension.”

In the U.S., Chung has seen a shift in cultural misconceptions about treating populations in poor countries. He remembered when he first began in 2002, there was a feeling among many American HIV experts that building up drug resistance would be a problem for people who couldn’t tell time and take their medications consistently. But this has not been an issue.

“It’s been a paradigm shift for people,” he said. “They’re not just saying, ‘We should prevent HIV,’ which is true, but also seeing that these lives should not be lost either.”

The post Living with HIV/AIDS: AIDS Researchers Say Work is Personal appeared first on Pavement Pieces.

]]>