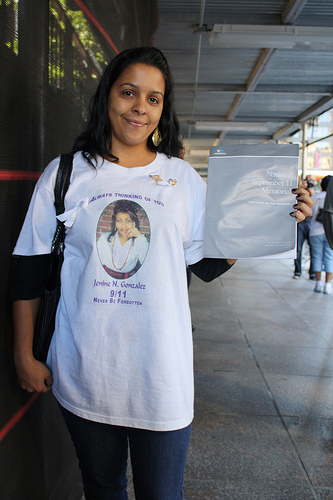

Jennifer Irizarry attended the 11th anniversary memorial service of the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. Photo by Alex Jung

There was no press melee, shouting matches, or political grandstanding. The families, friends, and colleagues of victims of the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001 gathered Tuesday to mark the 11th anniversary in a memorial service that was markedly quieter and more intimate than those from years past.

“We were freer to mourn in this service versus previous services because the cameras were absent,” said retired Air Force staff sergeant Alicia Watkins, who survived the attack on the Pentagon. She was there to remember her friend and fellow armed service member, Tamara Thurman, an Army sergeant. “This one was more intimate and I got to spend more time with family.”

“It was very serene, very quiet, a little different this year,“ said Jennifer Irizarry, who has attended the memorial every year. She was wearing a t-shirt with the photo of her cousin, Jenine Gonzalez, who was working at Aon when the attacks occurred.

Mourners wore small white ribbons pinned above their heart in honor of those who died.

“The service was very emotional,” said Alex Torres, who attended the service for Carlos Lillo, a paramedic who entered the North Tower just before it collapsed. “You would think that as time passes by, everything would be okay and it’s not.”

Ahead of the November elections, the memorial service itself was free of speeches by public officials who have been criticized in the past for manipulating the national tragedy for personal gain. Instead, the service began with officers of the NYPD bringing out the tattered flag recovered from the debris at Ground Zero and ended with the reading of the nearly 3,000 victims who died in the attacks.

“I was very happy there were no political speeches,” said Torres. “The last time I was here, it was too political.”

Even though access to the memorial was restricted to those directly affected by the attacks, there were plenty of fringe groups clustered in Zuccotti Park across the street from the Liberty Street entrance. Much to the chagrin of grieving family members, 9/11 conspiracy theorists, anti-Israel activists, and others who had little to no personal connection with victims of the attacks, saw the event as an the opportunity to grab the attention of anyone who would listen—and even those who would not.

“It’s a little disheartening because you’re competing with other tourists, protestors, and everyone in the city” said Irizarry in reference to the mélange of onlookers and protestors. “I feel like people don’t take it seriously.”

For bereaved family members, the memorial service was an opportunity to gather with one another and grieve with those who experienced a similar loss.

“It was so nice,” said Corinne Hargrave, a sophomore at NYU, in tow with almost 20 family members, who had come to remember her father, their brother and uncle, TJ Hargrave, the youngest of eight siblings. “It was a lot nicer this year that you could just stand around the pool.”

For Hargrave, who grew up nearby in Readington, NJ , there was special importance for her when she arrived as a first-year student at NYU last year.

“I lived in Hayden and my dorm looked straight onto the Freedom Tower,” said Hargrave. “I just got into college and the first thing I could see was the memorial. It’s always a constant reminder.”

Accompanied by her cousins and aunts, she was walking up the street to have lunch at Reade Street Pub & Kitchen, where they have lunch after every service.

“I’m so lucky my entire family lives in the tri-state area,” said Hargrave.

For affected friends and family members, years may pass, but the pain remains.

“For us every year is different, but the feeling is always the same,” said Irizarry.