Amid the din of construction, sirens, and car honks, the bells of Trinity Church in Lower Manhattan tolled majestically this morning in honor of the victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Few passersby seem to notice except for a small group of visitors gathered in the cemetery of St. Paul’s Chapel in the church for the annual ringing of the Bell of Hope.

In the weeks and months after 9/11, Trinity served as a safe haven for rescue workers, volunteers and mourning community members. The church, which sits directly across from ground zero, suffered little damage during the attacks.

“One hundred yards away, when the towers came down and the mushroom cloud destroyed the surrounding area, the oldest freestanding building on Manhattan — St. Paul’s — and its steeple was still there,” said David Sommerville, 74, an Episcopalian minister from Brunswick, Georgia. He volunteered at the church after the attacks.

Sixteen years later, the crowds have thinned, but the church continues its tradition of holding space in remembrance of that day and months following.

“I’m here for the memories of grieving that were ministered to me on that morning,” said Sommerville. “In the Episcopal church, we have a theology that says, ‘We know who we are because we remember. We know ourselves by our memories.’ I’m here helping keep memories alive. It’s like that famous quote, ‘If we don’t remember the evil things that were done, we will repeat them.'”

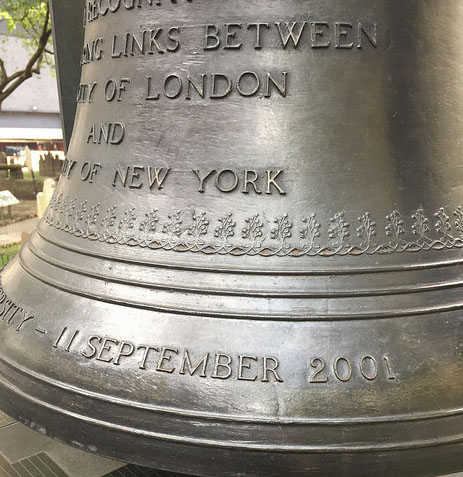

Reverend Doctor William Lupfer, the church rector, rang the bell in four strikes of five, the tradition of a New York firehouse bell code used to mark the death of a firefighter. After the ceremony, church employees, ministers, and security outnumbered their visitors. Two firefighters and one accompanying family member paused for a moment of silence inside the chapel. One guest lit a candle before taking a seat to pray. A few tourists paused in front of the permanent 9/11 memorial, spending a mere few moments with the memorabilia. Teddy bears, badges of fallen fighters and police officers, and a church volunteer’s notebook were among the items selected to represent the snapshot in time.

Fabien Taclet, 32, a tourist from France, said that although the crowds were thin, the attacks changed the world.

“I lived in London at the time and remember that the attacks marked a new era in which no one was safe anymore,” he said.

Outside the gates of St. Paul’s Cemetery, Gage Pullmeyer, 17, from Lincoln, Nebraska, paused aside a throng of people emerging from the subway. He used his phone to take photo of the new One World Trade Center building.

“I was only one at the time, but it was America’s greatest tragedy,” Pullmeyer said. “I wish I was older so I could remember. I think remembering makes us stronger. We are all so separated nowadays and there is so much hate going around. 9/11 was about hate, so this is bringing us together as a country. It’s important to reflect.”

At 9:50 a.m., a city fire department flag procession walked the perimeter of St. Paul’s heading toward the memorial site. Commuters momentarily made way for the procession’s large flags and accompanying family members in plainclothes. The usual lower Manhattan crowds resumed their Monday routines as the procession faded into the background of another workday.