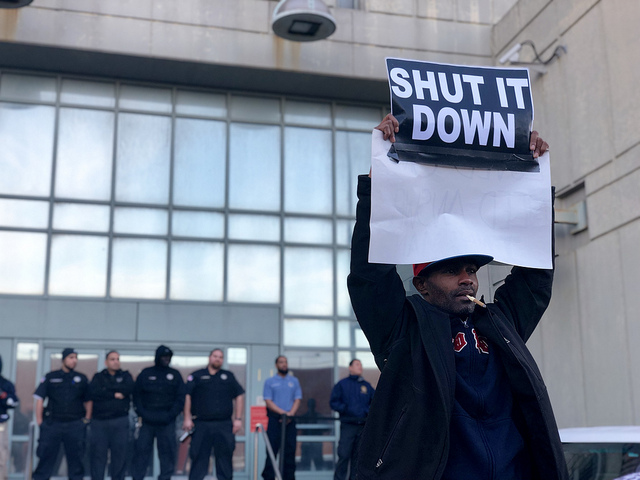

A protester holding a sign in front of prison guards at the front of the Metropolitan Detention Center on February 3, 2019. By Opheli García Lawler.

Metropolitan Detention Center is in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. It’s right next to the East River, and when it is cold in the city, this area is even colder. But it that hasn’t stopped activists in the city who have occupied the parking lot of the federal jail since February 1.

They have been there through freezing temperatures, altercations with NYPD, and the constant tapping of the men and women inside the jail, who had alleged they’ve been denied heat, hot water, and hot meals during the coldest months of the year.

Signs reading “Turn on the heat” and “We hear you, we love you” are still taped to a brick wall facing the front of the facility. Family members and activists spent their first days begging for the heating in a cold prison to be turned back on. When the heat and electricity in MDC was restored on February 3, after nearly three weeks without both, activists and family members did not leave. Rather, they remained occupying the jail, trying to push the conversation beyond just just this example. They believe inhumane conditions alleged at MDC could be a turning point for how incarceration in New York City is discussed.

Kei Williams is a leading organizer of the No New Jails NYC movement, and has spent over 26 hours in a row protesting at MDC. Williams and No New Jails NYC are working to organize shifts outside of MDC so that someone is there at all times of the day, until their demands are met.

The Twitter account for No New Jails NYC frames all of their organizing at MDC around more central ideas of abolishing detention centers. “If you’re also angry about Rikers, and angry about MDC, and angry about the Tombs, Brooklyn Detention Center, and the boat, we hope you’ll stay angry until we have a #JailFreeNYC where punishment is not the solution to poverty, conflict, or violence,” they wrote.

“In the long term, we know these conditions are multiplied across the millions of people who are incarcerated,” said Williams. “We know that this is not only federal jails. This is the story in city jails. This is the story in Rikers Island. MDC is not unique. The only thing that is unique is that there is a spotlight at this point and time.”

According to a study from the Prison Policy Initiative, 90 percent of the people incarcerated in New York are black and brown people. With at least 230,000 people in New York State’s carceral state, there is often a major intersection of advocacy between the groups who working to free those people– or at the very least, ensure that the conditions they are held in are humane. Whether the focus is prison abolition, criminal justice reform, or expanding conversations about who is put in jail, the crisis at MDC presented an opportunity. The situation became a conduit for all other jails and prisons in the city.hey wanted to take advantage of the local and national press to send a message to city and state leadership: no new jails.

“I have heard horrendous stories about people who have been detained in every jail, not just in New York, but across this country. But especially in New York state,” said Brittany Williams, who was one of the first organizers on the ground.

What she witnessed made her angry, but her experience and knowledge of New York detention centers meant that it was not new information to her.

“I was not surprised to hear that they didn’t have heat,” she said, “I was not surprised to hear that they didn’t have food, I was not surprised that to hear that people didn’t have their rights. Because that’s how, systemically, jails are operated.”

For other activists at the scene, MDC was an opportunity not only to talk about the pervasive human rights abuses committed in jails, but also to shed a wider light on who is impacted.

Linda Sarsour and a crowd of protesters standing at the back of Metropolitan Detention Center, making noise so the women at the back of the jail could hear them. February 3, 2019 by Opheli Garcia Lawler.

Ify Ike, who is an attorney and professor came to MDC after seeing posts about the lack of heat circulating on Twitter. She also wants to bring attention to the plight of women. About 100 female inmates are housed there.

“As an attorney who has done human rights work, including being on the ground in Ferguson – women are invisible in this conversation, ” she said.

There are fewer women being detained – 95.5 percent of New York State’s prison population are men. But the treatment of female prisoners is often just as severe as that of male prisoners, and their lack of visibility often means that fewer people are advocating for them. In order to hear or see the women banging on the windows of their cells, people protesting at MDC had to walk around to the back of the jail. For people like Ike, this was an opportunity to push for their stories to be included in media coverage.

The protestors said they will continue because there is nothing normal about mass incarceration. For now, they said they will remain outfront of the jail, hoping their message reaches the ears of government officials.