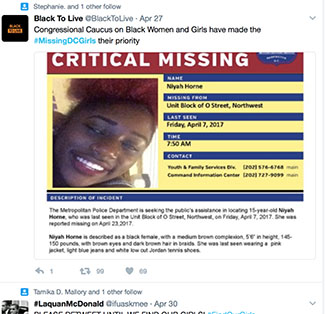

You probably saw the hashtag. You might have retweeted a link from Viola Davis, Andy Cohen, Gabrielle Union, or any of the other celebrities sending out appeals to find over a dozen missing teenagers. In March, #MissingDCGirls went viral, alongside the story of 14 teenage girls who all went missing in a 24 hour period.

But during a March 16th press conference, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser said there was no sudden spike of missing teens. The number of people reported missing in the city each year has stayed the same since around 2014 and 99 percent are found.

But there was a story here.

“A fake news story helped us expose a real problem,” said Angela Rye, political strategist and the CEO of IMPACT Strategies.

Across the country, girls and women of color go missing at a disproportionate rate and get less news coverage.

Nearly 800 juveniles were reported missing in D.C. this year, with the vast majority of those children coming home on their own or being located by police. There are currently 18 open cases for juveniles who have gone missing since the start of the year, all of whom are Black or Latino.

On April 26th The Congressional Caucus on Black Women and Girls hosted a town hall after a call for more federal funds to find the estimated 64,000 black women reported missing since 2014.

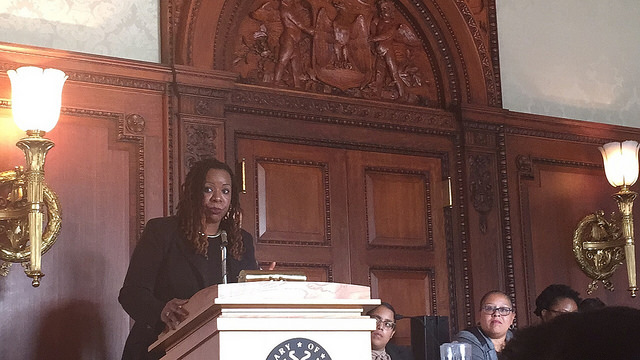

Rye served as the moderator of the town hall, which challenged the notion that all missing teens are runaways.

Every year from 2012–2016, there have been more than 2,000 juveniles reported missing.

The lines blur between kidnappings and runaways. Once missing, some end up in the hands of pimps and sex traffickers. Teens and young women and even boys are sex trafficked. Many other girls runaway and then begin a cycle of leaving home only to be sent back by law enforcement, over and over.

Advocates say the struggle is to keep eyes on this issue long enough to make some real, positive changes. In the weeks since, they have focused on keeping the story from being forgotten.

Co-founder of the Black and Missing Foundation, Derrica Wilson, spoke at the town hall on missing black women and girls on April 26, 2017. Photo by Rebeca Corleto.

Derrica and Natalie Wilson are sisters who founded Black and Missing Foundation nine years ago. The story of the 14 missing girls is hardly news for them.

“We’ve been sounding the alarm for years,” said Natalie Wilson. “Our black teenagers continue to be missing. Sex trafficking is happening now.”

One distinction that advocates for missing teenagers tend to emphasize is the difference between choice and force.

“Even for runaways, we have to ask, what are they running from?” Natalie Wilson said. “Most young girls don’t choose prostitution, or to runaway from home. They’re missing children.”

According to Natalie Wilson, escaping abuse was often a factor in missing girls.

The threat of abduction became a reality for the Scott family.

The teenage daughter of Linda Scott, the owner of a hair salon in Baltimore, Maryland, was almost abducted Her daughter, Kaniya, 16, called her, frantic and crying from a Baltimore public bus one afternoon. Three men had just tried to grab her and then cut off the bus with their vehicle when she got away from them. The three men had been plotting to take Kaniya. They scoped out the salon days earlier, pretending to be clothing vendors, and tried to talk to Kaniya, Scott said.

“I recognized the individuals and they asked for my daughter,” Scott said. “My daughter is 16-years-old, she doesn’t know these grown men.”

Scott immediately turned to the police, but has been disappointed with their response. She tracked down surveillance footage from a local business within eyeshot of the incident, and handed it over to the police. The police never contacted Scott to identify the suspects, though she knows what they look like.

“I’ve gone to the police station six or seven times in the last two weeks and nothing,” she said.

Scott said her daughter is scared, but doing okay. In the weeks after the near-kidnapping Kaniya is now monitored closely by her parents.

“As a teenager, she can’t go outside,” Scott said. “Now, her idea of having fun is me driving her around, or her dad.”

Some missing teens just need a safe place to run to.

Sasha Bruce Youthwork helps teens trying to flee pimps and get off the streets.

The organization tries to help kids reunite with their families when they can, but they know that in situations with abuse that’s not always possible.

“The systems are set up to blame somebody,” said founder Debby Shore. “You don’t want to blame the kids, but you don’t want to blame the parents either. We want to work with them if we can, to help people recover.”

Teenagers who can’t be reunited with their families can stay at one of their live-in facilities.

Advocates also encourage the policy of, if you see something, say something. Red flags to look for are teens out in public during school hours, and houses with “revolving doors”—a constant flow of multiple adults and teens coming in and out.

“We have instincts. Follow them,” said Natalie Wilson. She encouraged citizens to call 911 or the tip line on BAMFI.org her foundation’s website.

Derrica Wilson intends to push forward on the heels of this added media and public attention.

“What happened in D.C. four weeks ago did not just become and epidemic,” Derrica Wilson said. “But now it has a voice.”