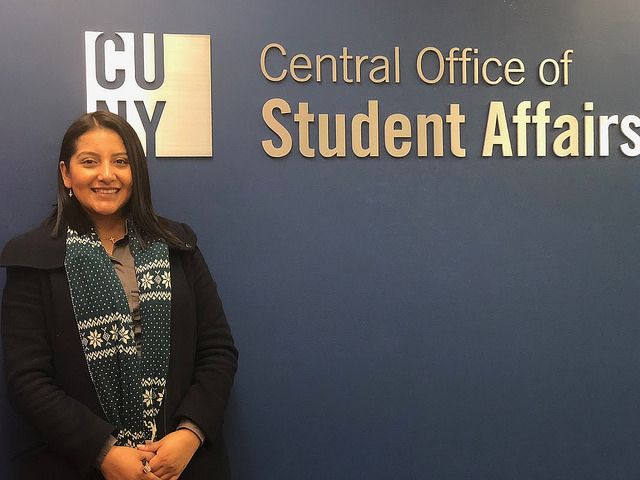

Monica Sibri is on the advisory board of the CUNY Dreamers, where she oversees activity and initiatives that those with protected and unprotected status engage in. Photo by Farnoush Amiri

Monica Sibri is a Dreamer who isn’t protected by DACA. Not because she didn’t apply or because she was “lazy,” as members of the current administration have stated, but because she came to the U.S. from Ecuador three months after her 16th birthday, making her ineligible for the program.

The term “Dreamer” originally came from the DREAM Act, which was a legislation proposed by representatives of both parties. In 2012, Barack Obama’s enactment of DACA was a compromise based on the proposals of the act and they, too, called themselves “Dreamers.” Young people like Sibri, although not protected by DACA, have used the word as a way to empower themselves.

“The way someone reacts to you when you say you’re a ‘Dreamer’ than when you’re undocumented is completely different,” Sibri, 25, said.”By saying that you’re undocumented, it assumes that you’re not in school or you’re this person who’s working in cleaning or you likely crossed the border, but when you say you’re a ‘Dreamer,’ people assume differently.”

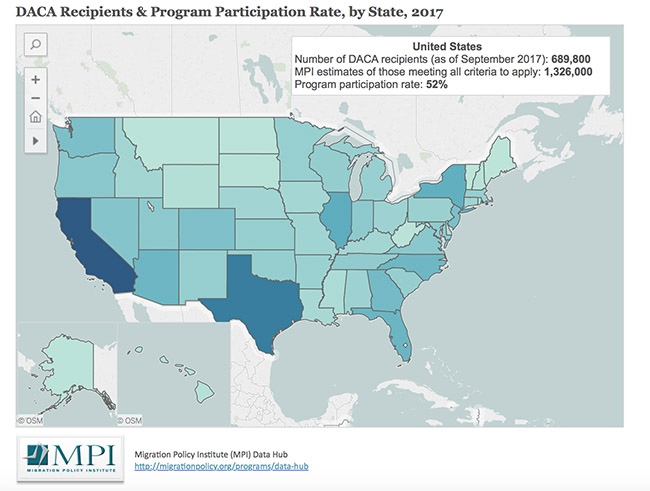

According to the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan, nonprofit think tank that studies global immigration patterns, an estimated 3.6 million people were brought to the U.S. before their 18th birthdays, making the focus on the almost 800,000 DACA recipients seem like an overlook of the larger issue of child immigration.

Sibri’s father decided to uproot their family when Ecuador’s currency changed in 2000 from the Ecuadorian Sucre to the U.S. Dollar, and he lost his managerial position at a candle company.

Her parents came to the U.S. to establish a life in Staten Island, separating the family for five years.

“I became an adult really young,” Sibri said. “I had to take care of my two younger sisters.”

When she learned she was undocumented and about the negativity surrounding it, she started calling herself a “Dreamer.” Sibri said that this helped her to confidently pursue higher education at the College of Staten Island where she graduated last year with a degree in American politics, policy and advocacy.

Since the law does not require one to disclose their immigration status, especially in educational facilities, Sibri maintained this persona, but never received any actual funds or special resources because of it. She explained that it created a shield against the stereotypes placed on undocumented individuals.

“My passion for creating a network of support begun with talking about the barriers I experienced myself. In college, I was often questioned about my immigration status and when letting them know that I was undocumented I got concerned looks, followed by a list of questions as to how I was in school,” Sibri said. “When talking about this, I learned through speaking to the network that this was happening in all spaces, from the school’s scholarship to the academic department, from the registration office to the office of financial aid, from the classroom to the soccer field.”

Sibri’s solution to this was to create the City University of New York Dreamers, an organization for those with protected and unprotected status in the college system. Today, she serves on the advisory board for the program and has gone on to help initiate a larger group for “Dreamers” after she graduated from college and realized the same resources weren’t set up to foster undocumented individuals after graduation.

“DACA recipients often assume that I am a DACA recipient because of my work, and often when they learned of my status, they share tears with me,” Sibri said. “We just cry together.”

She said that she knows other undocumented students who have adopted the identity “dreamer” or assumed the societal benefits of a DACA recipient, but that it becomes much more complex upon graduating from higher education.

“(Post-grad), undocumented students begin to realize there are some things they have to navigate around and that there are potential barriers to achieving their dreams,” said Cristina Velez, staff attorney for the Immigration Defense Fund at New York University.

Sibri has been pushing against that narrative through her work at a nonprofit called Ignite, which aims to empower college-aged women to become active in their community and eventually run for office.

“I thought to myself, I’m undocumented, I might be in the process of getting deported. What do I do in the meantime?” Sibri said. “Democrats and Republicans in office are not representing me so I have to train the next generation to represent their communities like they’re supposed to.”

Now, Sibri and the more than 11 million undocumented individuals in the U.S. have nothing to do but wait — wait to see if a clean DREAM Act is passed or if they have to bargain a possible road to citizenship and protected status with Republican efforts to get a border wall and an end to “chain migration.”

“I think there is a glimmer of hope right now that if DREAM Act does pass then some (undocumented individuals) would finally have some opportunity to work in the United States and to have status,” Velez said. “For them, probably seeing the benefits of DACA for their peers must be very destructive and difficult at times. And I’m sure it would be even more of a blow if the DREAM Act did not come to pass.”

For Sibri, it will be more than a blow. She is part of what she calls a “mixed-status” family; her younger brother is a U.S. citizen while the rest of her family is undocumented. As the March 5 deadline approaches for congressional agreement on the future of “Dreamers” and consequently undocumented individuals alike, Sibri and her family are at peril of being separated once again. Deportation has become more of a reality for undocumented individuals than ever before. Sibri, said she constantly lives in fear of deportation and options may be running out.

“As much as I would love to continue fighting, my timeline in New York is dependent on us getting some sort of legislation in the next five years. If not, I will have to self-deport,” Sibri said, referring to undocumented individuals leaving a country where they could face deportation before ICE reaches them. “What else can I do? We are living day by day without being able to look ahead.”