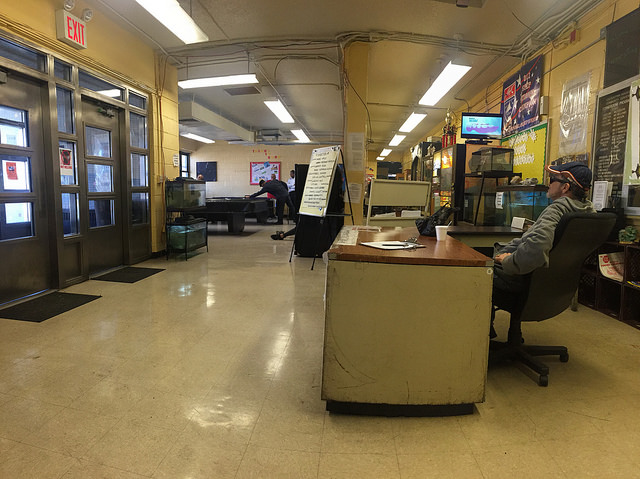

The entrance of the Pink Houses Community Center, a safe haven for residents of the Pink Houses, deemed one of New York City’s most dangerous neighborhoods. Photo by Amina Srna

Francisco “Chico” Gonzales, 62, leaned against the fence outside of the Pink Houses Community Center in East New York, Brooklyn on a cold and bright March morning, smoking a cigarette without his hands while his fists balled up for warmth inside the pockets of his hoodie.

“Manslaughter is 15 years, let them give him the 10,” said Gonzales of the recent sentencing recommendation for former NYPD officer Peter Liang who fatally shot resident Akai Gurley in the unlit stairwell of one of the Pink Houses in 2014. Gurley, a tenant of the apartment complex, was coming down a darkened stairwell, because the lack of building maintenance allowed bulbs to burn out and elevators to stall, when Liang, frightened and with his gun drawn, shot into the darkness and killed Gurley.

Liang was convicted of manslaughter in February and on March 23rd, Brooklyn D.A. Kenneth Thompson asked Supreme Court Justice Danny Chun to spare Liang prison time. Instead, Thompson recommended five years probation and six months house arrest, compared to the 15-year sentence that Liang faces for manslaughter.

For the tenants of the Pink Houses, one of the most dangerous housing projects in New York City, the upcoming sentencing hearing is an opportunity for the community’s safety concerns, such as poor maintenance which leaves hallways permanently darkened and elevators stalled, to be vindicated.

“It was not justified,” Gonzales said. “They say his gun discharged but still, he didn’t have to have his gun out.”

A long-time resident of the Pink Houses, Gonzales supports making an example out of the Liang trial. He hopes it would help to change the public perception of the NYPD officers, who, in his experience, always seem to come when it’s too late.

“I was shot right behind this building in 1975. Over a gold chain that wasn’t even real gold,” said Gonzales. “By the time they show up the crime has been done already, the person is shot, dead or whatever. They just come to investigate and get information, if there’s no witness then the guy gets to get away with it.”

Francisco “Chico” Gonzales, 62, sits at the makeshift reception desk at the Pink Houses Community Center. Photo by Amina Srna

Gonzales finished his cigarette and walked back into the Pink Houses Community Center, where he took a seat behind a weathered fiberboard desk, a makeshift reception. He swiveled his pleather office chair towards a t.v. and turns up the already loud volume for the news. To his left, an overweight man with a graying afro is fast asleep in his wheelchair.

The entire décor of the community center seems frozen in time, a haphazard amalgamation of dated grey and dark brown office furniture that makes the whole place (aside from two brand new violet pool tables) look as though it was built in the 70s and promptly forgotten.

This archaic presence is compounded by the residents that walk in on weekday mornings for the free lunches that the center provides for the senior citizens of the Pink Houses. Gonzales greeted his neighbors in between ruminating on the District Attorney’s recommendation.

The core of the problem for Gonzales is that the police officers sent to patrol the Pink Houses, one of New York City’s most dangerous housing projects, are largely unfamiliar with the area and inexperienced. Liang was no exception.

“Coming out of college, they’re not really street wise,” said Gonzales. “Show people cops that will know the neighborhood. That Chinese cop, he didn’t know this neighborhood.”

Since February, Gonzales’s sentiments have echoed throughout the news. Coverage and commentary of the trial and impending verdict have become platforms to scrutinize anything from police academy training to racism towards African Americans and Chinese Americans.

“He was a minority, so we are doing everything we can to show the community that we’re going after the cops,” said Noel Lazarus, the director of the Pink Houses Community Center. “To compound that, the D.A. now is saying that he should not get any time in prison. So why you go through a trial and then in the end you say he shouldn’t? He should have never been tried, he was made a scapegoat.”

Lazarus said that the 2014 incident of Liang shooting Gurley in a dark stairwell was not an isolated circumstance, that in fact, Liang’s fear is a daily reality of the residents who live in the Pink Houses, where burglars black out stairwells in order to rob residents.

“I was speaking to guy a couple days ago, this guy told me he got robbed three times, right in his building, so he got a gun,” said Lazarus.

“He says, coming up the elevator, the wind blew a door shut and he said he fired five shots, at no one. There was no one there. He said he never carried that gun again, and he’s talking about three four years ago. Because if there was someone there, whether someone to rob him or not, he would have shot them.”

The contrasting sentiments of the residents of the Pink Houses are echoed throughout the neighborhood. Outside, the streets that surround the Pink Houses are markedly empty, the glaring noon sun casting stark shadows on sidewalks. Katrina Wilson, 32, stood in a small sunlit patch a few blocks away from the Pink Houses and waited to catch the M14 bus to work.

“He could have asked a question before he shot him,” said Wilson. “I don’t think it was prevailed as justice. He could have served more time than what he is serving now.”

Further up, on Euclid Avenue, Joe Lewis, 40, sat on a picnic table at the deserted Cyprus Hills Playground, watching two men who met by the bathrooms for a drug deal. Lewis has been following the trial and does not know what the fair sentence should be. His concern is that Liang has been made a token for police brutality, and in the process, been stripped of his humanity.

“He lost everything he had,” Lewis said. “He lost his title as a police officer and as he progresses his life he’s going to be haunted with this. He shot someone who was unarmed. He’s scared for his life, he killed an innocent kid.”