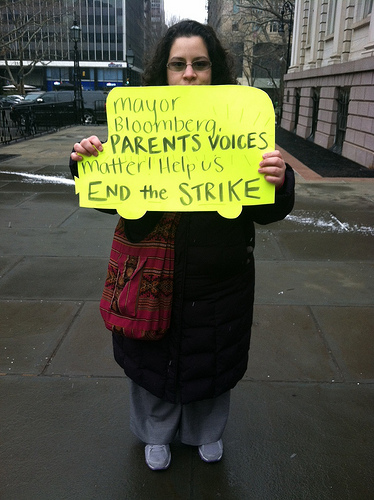

Zsuzsa Schuster, 34, of Jackson Heights, Queens, holds a sign outside City Hall Tuesday afternoon calling for Mayor Bloomberg to negotiate with bus companies and drivers’ unions. Since Jan. 16, bus drivers have been on strike amidst a labor dispute between the unions and the city. The Bloomberg administration has refused to enter negotiations with the main drivers’ union, Local 1181 of the Amalgamated Transit Union, and the bus companies. Photo by Timothy Weisberg

At 5:30 a.m. every morning, Zsuzsa Schuster wakes up her six-year-old son for school. She lives in Jackson Heights, but due to overcrowding, has her son enrolled at a school in Long Island City, Queens.Schuster, 34, then drives to work on 23rd Street and Madison in Lower Manhattan.

Her son, who suffers from asthma, would normally take a bus near their home, but because of the recent strike by New York City bus drivers, she has to wake him up earlier in order to get him to school and then to work on time.

“I still get to work an hour late,” she said.

Since the bus strike began Jan. 16, more than 160,000 students have had to find alternative ways to class since drivers walked out on the job in an ongoing dispute between the city and main drivers’ union, Local 1181 of the Amalgamated Transit Union. While none have been more affected by the bus strike than special-needs students, who often have to travel the farthest to get the services they need, the strike has placed an unprecedented burden on parents of the remaining two-thirds of children that rely on the bus service to get to and from school.

Schuster often has to pull her son out of school and put him in daycare when she has all-day business meetings with upper management.

“How am I supposed to tell my boss that I’m not going to a meeting because of a bus strike?” she said. “They are already giving me the allowance to come in late every day.”

The city has offered to reimburse parents up to $200 a day for car services, but many are unable to front the money, said Isaac Carmignani, Co-President of the Community Education Council in District 30.

“It doesn’t reimburse you for the loss of employment time,” he said.

Carmignani, who has a daughter in high school, says she has to take public transportation as a result of the bus strike.

And for parents who can’t front the money for cabs or car services, many remain skeptical about having their children ride the metro or city bus to get to school.

“You’re afraid. You’re afraid for your child taking a city bus,” he added.

At the core of the labor dispute is economically and financially driven. In an effort to reduce costs, mayor Michael Bloomberg is attempting to take bids for new contracts on the 1,100 special education routes in the city, without providing job security or protection to current driver union members. In essence, the drivers could be laid off if their company does not win the contract bid. These seniority-based job guarantees are where the two sides remain far apart.

Yet the Bloomberg administration continues to refuse to take part in negotiations to end the strike, arguing that negotiations should occur between the unions and bus companies.

“Postponing the bids would guarantee that the same billion-dollar contracts we have now stay in place next year,” Lauren Passalacqua, a spokeswoman for Bloomberg, said in a statement. “The union is irresponsibly holding our students and city hostage over issues that can only be resolved by negotiating directly with the bus companies.”

More than two weeks into the walkout, many parents are worried that there is no resolution in site.

“That’s what’s so shocking,” Carmignani said. “It’s as if this is now business-as-usual.”

Public Advocate Bill de Blasio criticized the mayor’s response to the dispute, and believed it is the mayor’s responsibility to deal with labor relations’ issues and bring the parties together.

Public Advocate Bill de Blasio speaks at a press conference held Tuesday afternoon at the steps of City Hall. De Blasio, along with parents and other advocates, have called upon Mayor Bloomberg to end the labor dispute. Photo by Timothy Weisberg.

“For parents in this city, after 15 days, the sense of disbelief has grown,” he said.

De Blasio, along with parents and other advocates, implored the Bloomberg administration to come back to the negotiating table and end the labor dispute at a press conference this afternoon in front of City Hall.

“There’s no reform that you justify by ending bus service for kids in this manner,” he said at the press conference.

For Schuster, the arduous process of getting her son to school every day will only continue until the bus strike is over and drivers get back behind the wheel.

“I don’t have a choice,” she said impotently.