Protesters gather near the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building to call for more aid to be sent to storm-stricken Puerto Rico. Photo by Amy Zahn

As Puerto Rico continues to feel the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, New Yorkers with ties to the island are experiencing a mounting sense of desperation, not knowing how to help, and in many cases, unable to contact their loved ones at all.

“It’s so desperate. We are all anxious,” said Puerto-Rican born New York resident Juan Recondo at a demonstration to rally support for the island yesterday. “My wife is crying all the time and I completely understand — she hasn’t spoken to her brother for more than a week.”

Recondo, like many of his fellow demonstrators, feels paralyzed in the wake of the storm’s destruction. At least 16 people have died, and millions are without power, clean water and gas, according to a CNN report.

“There’s no way we can help,” Recondo said. “Our hands are tied. This is the only way, trying to get involved in this type of movement.”

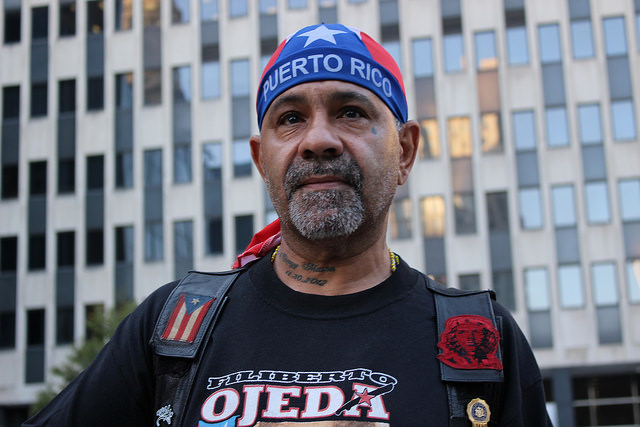

Juan Recondo attends a rally in support of the people of Puerto Rico in Lower Manhattan yesterday. Photo by Amy Zahn

Recondo, along with over a hundred other protesters, gathered in Lower Manhattan to call for more aid to be sent to Puerto Rico and to condemn what they see as a slow response to the disaster by the U.S. government.

“I haven’t heard from my family at all, my whole family,” said protester Anthony Zayas, wrapped in a Puerto Rican flag. Aside from his mother, who lives in New Jersey, Zayas’ entire family is in Puerto Rico.

The state of New York is home to over a million people who identify as Puerto Rican, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the largest number in any state. There are over 5 million Puerto Ricans on the mainland U.S. in total, making them one of the largest Latino groups in the country, second only to Mexicans.

“People are praising Trump, but you know what? He did it too late. It should have been done immediately,” Zayas said, referring to Donald Trump’s temporary waiver of the Jones Act last week, eight days after the storm hit. “We’re American citizens, too.”

The Jones Act, passed in 1920, requires all ships transporting goods between U.S. ports to be built by Americans, and primarily manned by them. Trump lifted it for 10 days to facilitate shipments to the storm-ravaged island.

But despite the difficulties of assisting 3.4 million people — the population of Puerto Rico — there are ways to tailor relief efforts to be as helpful as possible, or at least avoid making things worse unintentionally.

According to Tony Morain, communications director for Direct Relief, a nonprofit that provides medications to hospitals and other health centers in disaster areas, it’s important for people to be mindful about the kinds of supplies they send.

In natural disasters, he said, it’s common for a shortage of truck drivers to combine with an influx of supplies trying to reach an area, creating a bottleneck in aid transport. After the Haiti earthquake in 2010, Morain explained that well-meaning people sent nonessential items like stuffed animals and toys, which can clog up ports and slow the distribution of life-saving supplies.

Morain also advised against sending winter clothes, since Puerto Rico has been experiencing high temperatures. Water, food, gas and medicine are the essentials, he said.

As far as longer term help goes, Morain thinks awareness is Puerto Rico’s best bet at recovery.

“Keep this in the news,” he said. “It’s always the case that first people talk about the wind speed of the storm, and then they show palm trees swaying, and then things go dark for a bit because there’s no communication, and then we start hearing stories about how devastating the first response search and rescue is … and then it becomes communities that have been forgotten.”

Robert Perez waits for a pro-Puerto Rico rally to start in Lower Manhattan yesterday. Photo by Amy Zahn

Puerto Rican Americans like protester Robert Perez, whose aunt and sister are stuck on the island, are unlikely to forget anytime soon, and he hopes the government won’t either.

“After the pressure’s put on the government, maybe Mr. Trump will do something,” he said.