Had Oswaldo Brasile’s gear been any more patriotic and “American” in nature, he might have been dressed as Uncle Sam.

The 47-year-old resident of Sao Paolo, Brazil, decked out in a red, white and blue polo shirt inscribed in cursive with the words of the Declaration of Independence, had just flown to New York from Orlando, where he’d been attending business meetings. Now, on this overcast morning in Lower Manhattan, he stood just a few blocks from ground zero where events commemorating the 10th anniversary of 9/11 were underway.

“It seems like a very appropriate shirt for today,” said the Brazilian. Every few seconds another passerby would pat his back or direct a ‘thumbs up’ his way.

Brasile, who described his job title as “President of the Institute of Internal Auditors” in Brazil, said he’d traveled here to “remember and to see how deep the impact [of 9/11] was on people’s lives.”

“And also to give Brazilian support for the U.S.,” he added. “It’s my way to do something.”

On blocks surrounding the 9/11 Memorial that was unveiled here Sunday, foreign visitors like Brasile comprised a sizable chunk of those who packed its sidewalks.

Like their American counterparts, foreign citizens said that they, too, had come to honor the victims and their families. But many of these foreigners also seemed to revel in unofficial roles, self-declared ambassadors of their home nations. They were eager to express their neighbors’ and native countries’ solidarity with America.

Unlike Oswaldo Brasile, whose surname was the only immediate clue as to his country of origin, it was often easy to determine one’s nationality by merely eyeballing the person’s attire.

One example of this was Paul Cull, a 46-year-old with Julius Caesar-style black hair and a black polo shirt featuring the words “New Zealand” near the top. Cull is from Christchurch in the southern part of that country, a historic and scenic city with a river intersecting its center. It’s a land with majestic mountains, about as distant from New York as anyplace on Earth.

“[9/11] was a very significant event in world history, whatever your political views,” said Cull, who noted that he’s in the U.S. doing missionary work unrelated to Sunday’s events. “It has molded and changed the planet.”

In February, an earthquake struck Southern New Zealand with an epicenter near Christchurch, devastating Cull’s community. The disaster claimed nearly 200 lives, and resulted in the nation’s first ever declared State of Emergency.

Cull said his close proximity to that trauma made his attendance Sunday essential.

“We’ve been through our own disaster and can sympathize with the loss of life,” he said. “It’s tragic.”

Along Broadway Street, throngs of foreign journalists shifted about with camera equipment and microphones, jockeying for space and conducting interviews in languages as disparate as Spanish and Mandarin, Japanese and French. Their presence highlighted the international spotlight on the day’s ceremonies.

One such foreign reporter was Christian Hauffman, a morning show news anchor in Berlin, Germany. A tall blonde man of 37, Hauffman, gripping a yellow microphone and sporting a bright red shirt with the words “104.6 RTL: Berlins Hit-Radio” said there’s much interest in Germany surrounding the memorial in Manhattan. He said there were moments of silence in Berlin today to honor the 9/11 dead, adding that many Berliners were attending church to commemorate 9/11.

Hauffman attributed his country’s attention here and his station’s media coverage, by extension, to the climate of uncertainty and alarm that pervaded Germany a decade ago, in the attacks’ aftermath.

“People were frightened, buildings were evacuated,” recalled Hauffman, who was working for another Berlin radio network at the time. “Nobody knew if there were planes that would hit our buildings. People were frightened.”

To most foreign citizens who’d come to pay their respects, however, the reasons for being at ground zero Sunday were more basic.

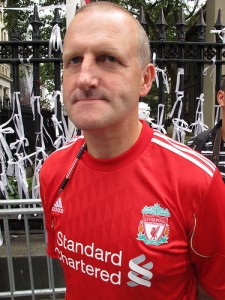

Sean Sheosarah, wearing a red Liverpool soccer jersey and gnawing on a toothpick, stood in a long, narrow, cordoned-off security line leading to a police checkpoint, awaiting entry into the memorial’s events. A burly, shaved-headed construction worker from Ireland who resides in the UK, Sheosarah, 42, had flown to New York from London solely for this purpose. He said little, but chose his words selectively: he’d be in the U.S. just four days, he said. He’d lived in Boston on 9/11.

Asked why he ventured across an ocean just to be here Sunday, Sheosarah shrugged in agitated fashion, as if the answer were obvious.

“It’s [about] respect, isn’t it?” he said, in a sharp Irish twang. “If you respect something, what’s the difference if it’s a mile away or a million miles away?”

He then removed the toothpick from his mouth, just as a ceremonial bugle began ringing out over Lower Manhattan.

“Distance,” he said, “Has nothing to do with it.”