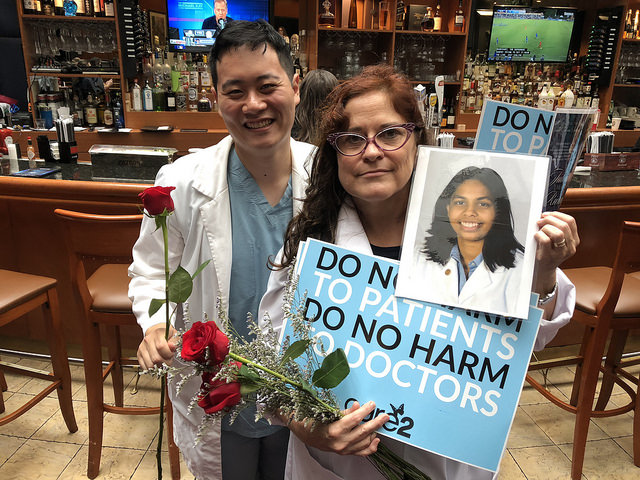

For National Suicide Prevention Week, doctors lay flowers, signs and pictures at the sight of where one of the their colleagues took her life near Mount Sinai West Hospital in Midtown. Photo By Levar Alonzo

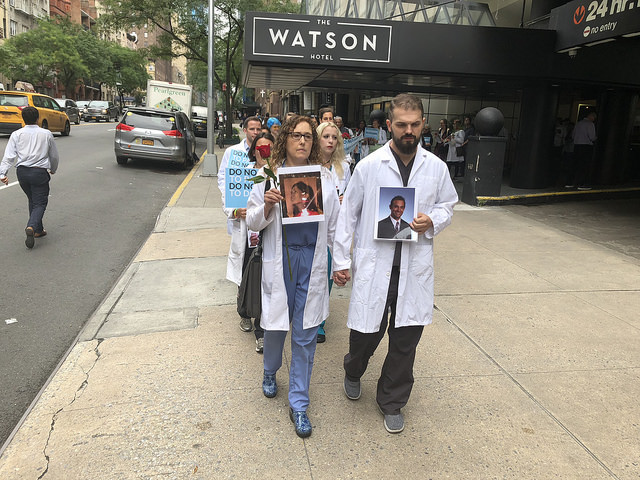

In recognition of National Suicide Prevention Week, physicians clad in white coats held roses and pictures of departed colleagues who battled mental illnesses. They marched silently yesterday, past Mount Sinai West Hospital in Midtown to a spot just blocks away from the hospital where one of their own tragically ended her life.

“We are here to honor our brothers and sisters that felt like they had no choice, but to take their lives,” said Dr. Lisa Goldman, of Tucson, Arizona. “We want to just let them know we still think about them and miss them.”

Lisa Goldman, M.D., holds up a picture of her friend Nehal Shah, M.D., who tragically took her life on the day the two were suppose to go to Guatemala for a graduation celebration. Photo by Levar Alonzo

Members of the group who came from across the country also held signs that read “Do No Harm to Patients, Do No Harm to Doctors.” “Do no harm” is significant to a doctor, as it is part of the Hippocratic oath to protect those they serve. These doctors said they want the same pledge to be extended to them.

The high rates of doctor suicide they believe are increasing because hospital systems severely overwork their physicians, which lead to medical errors, and there is no outlet to release stress. Doctors are fearful to go to their bosses with their issues because it makes them look unfit to perform.

According to Dr. Deepika Tanwar of the Harlem Hospital Center who has studied physician suicides over the past 10 years, 300 to 400 doctors a year take their lives, which is higher than the suicide rate of the general population.

Dr. John Danyi of Virginia attempted suicide over a year ago. He said that he had no way or time to get his frustrations out.

“This is not an issue that is confined to physicians alone, but it’s worst in us because there are more stresses and fewer outlets for those stresses,” he said. “The most common way to deal with the stresses and despair you see is to just soldier on. That’s what we are taught.”

Danyi added that since his attempt to take his life he has not been able to return to practicing medicine.

“It’s like I’m blackballed,” he said. “The Physicians Monitoring Program won’t let me start practicing again. You’re punished more if you try to harm yourself than if you try to harm a patient.”

According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, factors that drive doctors to suicide are workload, work inefficiency, lack of autonomy and meaning in work, and work-home conflict.

Doctors silently march towards Mount Sinai West Hospital in midtown holding hands roses and pictures of their friends who committed suicide. The doctors want to bring awareness of the increasing number of doctor suicides. Photo by Levar Alonso

Dr. Pamela Wible of Eugene, Oregon, who organized the event, said she has been speaking with her peers about their issues for six years. She set up an anonymous hotline and has collected 1,000 accounts of doctor suicides.

“We are not protected by labor laws or confidentiality laws,” she said. “If you go to a doctor they can look up your file and judge your ability to work on what troubles you. The post-traumatic stress disorder that these doctors deal with daily, from having to see your patients died or tell a family they lost a loved one takes a toll on one’s psyche.”

The problems faced by these doctors start at times when they are in medical school.

Danny Lee, 27, a medical student at Virginia Commonwealth University, said that a recent survey in his class of 200 revealed about 10 percent were suicidal.

“It’s the whole culture of medicine that has to change as much as they give us counseling and social activities,” he said. “The culture of medicine is toxic, it really has to change from a systemwide level and just how it’s taught.”

Wible wants patients to also try to understand that as much as society views doctors as superhumans, they are simply humans underneath.

“Be nice to your doctors,” she said. “They are humans. They might be dealing with a traumatic situation, just in the room before they come to see you and smile with you,” she said. “Nothing hurts to just have a conversation with your doctor.”