Through the windy roads of Oakland, California, Joaquin Miller Elementary School is perched at the top of a mountain, hidden by a lush forest. In March of last year, the K-5 elementary school was flooded with students ready to finish classes before spring recess.

But California Governor Gavin Newsom announced this year’s school vacation could last until Fall.

In the Golden State, 1,039 Coronavirus cases have been confirmed and a total number of 19 deaths. In the Bay Area, around 675 cases have been identified. Last night, Governor Newsom gave a mandatory order for all Californians to self-isolate, in addition to a “shelter in place” policy that was enforced Tuesday. The policies are some of the strictest methods enforced in the U.S., asking all residents to stay inside their homes.

In Alameda County, Oakland Unified School District said they would move to remote learning for the duration of the lockdown. Last Monday, teachers were warned they may not have classes for the remainder of the school year.

Sylviane Cohn felt a sense of pain when she taught her last class at Joaquin Miller Elementary for the foreseeable future.

“I miss them and I feel super useless,” said Cohn, 35. “I just feel so helpless in terms of how I am supposed to fulfill my professional obligation to make sure these kids come out knowing how to read.”

She said she is worried about students who have difficulties learning on their own.

“I have to figure out how to be an online educator. How I manage to reach the kids I need to reach, some of the most vulnerable students in the school,” she said. “So that learning can continue.”

As kids struggle to begin online classes in Oakland, there is a digital divide for low-income families. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, 22% of low-income households with school-aged children had no internet access, and Bay Area families making under $59,000 reported having less internet availability than wealthier families. In Bay Area public schools, inequality is a common issue.

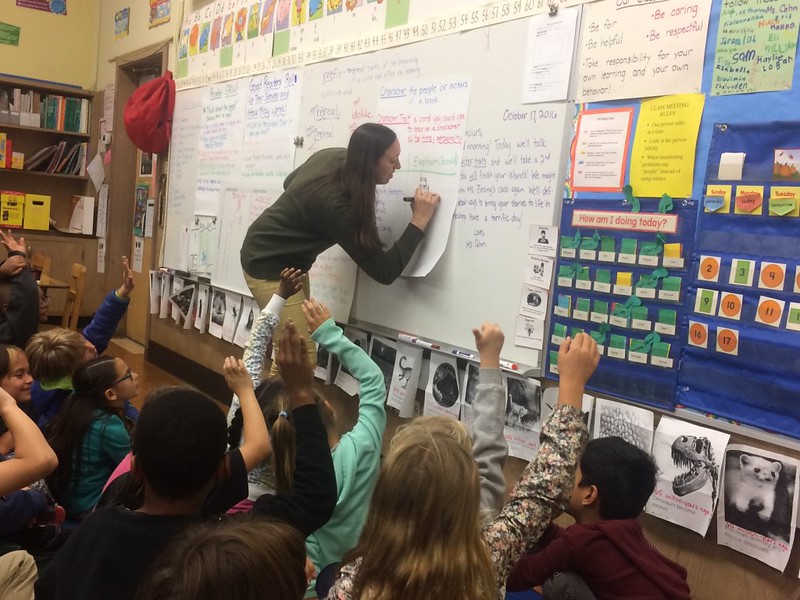

Joaquin Miller Elementary School, Oakland Hills, California. Photo by Joaquin Miller Elementary.

At Joaquin Miller Elementary, they are trying to decrease the gap among students.

“We have allowed families to check out Chromebooks from the school so if families don’t have a computer they can get one,” Cohn said. “We have tried to publicize that Comcast is delivering two months of free internet to families who need it.”

But she said they can’t control family circumstances and some students will fall behind. She said there are parents who can’t afford to stay at home.

“Between kids who have families at home who have the time and capacity to work with them and support their continuing learning, versus kids who are taking care of themselves at this time because there is no one who can support them,” she said. “There are kids who have resources at home, but then there are kids who don’t have resources and will watch TV all day. I think that is going to be the largest equity gap.”

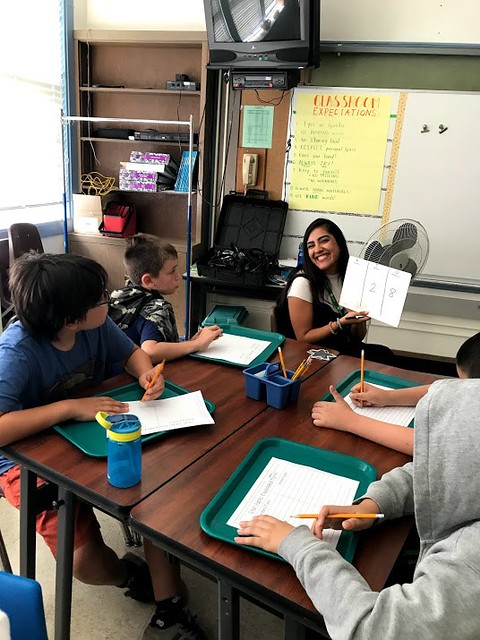

Zoe Lieberman experienced this disparity with her Joaquin Miller Elementary class. Lieberman, 27, began teaching online this week, but said that half of her students didn’t show up for their first class.

Zoe Lieberman teaches 3rd-5th graders at Joaquin Miller Elementary. Photo by Joaquin Miller Elementary.

“I am happy because I did have half of my class show up to our video chats, but that is only half of my class,” she said. “How many kids are going to have access to technology? There are many different school districts and socio-economic boundaries here. These are all these things that teachers are worried about right now.”

Lieberman’s concerns are common across the nation.

Mayor Bill de Blasio expressed distress in closing New York City’s public schools in reaction to the spread of the Coronavirus. The nation’s largest public school system serves around 750,000 low-income students, and doubles as a place for students to get meals and have access to technology.

But public schools will be closing down this week to lessen contamination, and will switch to online learning on March 23. Teachers will be asked to come to work for training on remote education, and New York City schools are offering computers for students who need them.

For Oakland students, Lieberman said they are trying to help by being available for support.

“I wish there was more that we could do but I am trying to make myself available online,” she said. “Next week I am setting up office hours if anyone wants to video chat, or do a lesson.”

She said there will be unique challenges for students beginning online education.

“Our community is different,” Lieberman said. “A lot of our kids don’t have the ability to independently log on, and answer the questions. Some of them might not be able to read the questions. There are challenges and it’s hard to accommodate everybody.”

Families are also worried about their children’s mental health while learning remotely.

“This morning was the roughest morning for the kids, because it sank in that they aren’t gonna see their friends,” said Anne Hurst, 46, a mother of two. “They said they miss their friends and their teachers and they don’t want to do homeschool anymore.”

She said that there has been emotional distress for her family while staying at home, but they are trying to remain positive.

“They are sad right now,” she said. ““We take one day at a time, and try not to think too much about the future, because it is unknown. It feels too scary, so just focus on doing the best with what you can do today.”

And Cohn, who may not see her K-5 classes for the rest of the school year, said that her students were equally devastated about missing their friends.

“They seem to have a clear understanding that play dates were gonna be cancelled for the indefinite future and that was scary for them. It was both wonderful and horrible that they were devastated by the notion of not going to school. We love structure as humans, and that was taken from them.”